As a student of both television and urban politics (admittedly an odd combination), I was struck by the prominent role played by the Seattle skyline. The image seemed to suggest, in short, that it mattered where this relationship drama was set. The inclusion of Seattle’s skyline (along with, of course, the ubiquitous Space Needle) meant something to the show’s fan base of college students. But what was that “something,” anyway?

Further “study” (i.e., watching TV, surfing YouTube) confirmed that Grey’s Anatomy was by no means alone. Establishing shots of glittering city skylines and vibrant urban street scenes proliferate on contemporary television—to the point where one might conclude six decades of rapid suburbanization have been abruptly reversed. Not quite. If many American central cities have stopped hemorrhaging residents in the last five years, population growth remains, as it has since the New Deal, a largely suburban phenomenon.

So what explains the seemingly sudden “back to the city” movement on American television?

One answer is that TV never left actually the big city. And this is true enough. The fate of the American metropolis has been a key subject of dramatic television for decades. Yet, until recently, as Steve Macek points out in his insightful new book, Urban Nightmares, media representations of the city have most often dwelled on the negative, depicting with seeming relish an urban America caught in a never-ending cycle of crime, drugs, and moral decay.[1]

During the Reagan era, for instance, Escape from New York presented moviegoers with a dystopian urban future in which the authorities had exhausted all solutions to the “urban crisis” and had instead turned the entire island of Manhattan into an open-air prison.

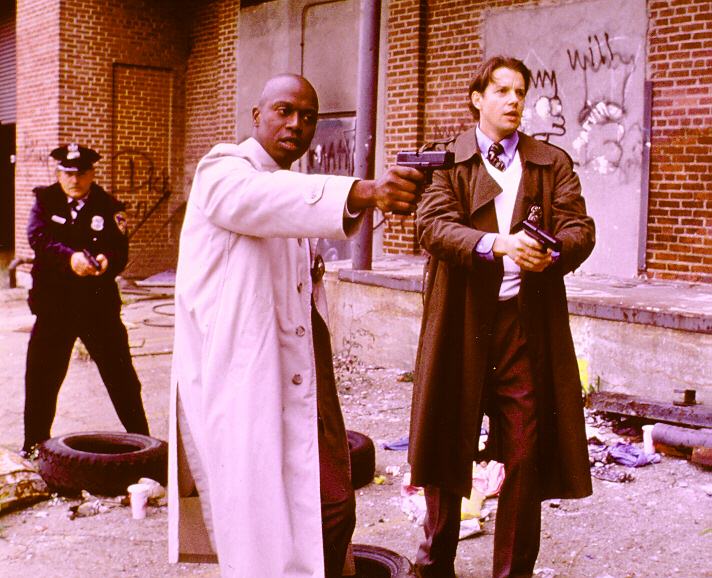

On television, 1980s cop dramas like Hill Street Blues and Homicide: Life on the Streets mined the same ideological vein, if from a slightly less reactionary position. On these shows, viewers were presented with an urban landscape bursting at the seams with disorder and deviance—the de rigueur drug dealers, gang bangers, and serial killers—all set in a crumbling urban landscape marked by graffiti, abandoned buildings, and homeless encampments.

If our heroes in these Reagan-era shows (almost always cops and prosecutors) gamely labored to sew up the moral and social fabric, suburban viewers knew their efforts would be for naught. There would in short be no solution, no stepping back from the urban brink.

For his part, Macek argues that these bleak media representations of the American city amplified conservative political discourses about the causes of the “urban crisis.”

Thoroughly mystifying the role global economic restructuring played in undermining urban economies, conservatives instead blamed the city’s poor for their own poverty, along the way constructing menacing (and thoroughly racialized) folk devils like the “welfare queen” and “drug kingpin.” In doing so, these discourses labored to consolidate white suburban support for “get tough” policies like welfare reform and the patently racist “war on drugs.”

To be sure, such reactionary images of a decaying, pathological inner city persist on American television. The opening sequence of Jerry Bruckheimer’s CSI, for example, trades explicitly in urban nightmares, interspersing shots of the Vegas strip with quick cut images of firing handguns, yellow-taped murder scenes, and forensic scientists looking thoughtfully at decaying bits of flesh.

Fans of the franchise know that in CSI-land, the streets of Vegas, Miami, and New York play host to the most gruesome murders imaginable, with human corpses offering up the secrets that eventually allow investigators to catch the bad guys. In such shows—NBC’s Law & Order franchise comes to mind as well— the urban landscape is still presented as a threatening space of violence, deviance, and moral decay.

Yet, it seems to me that dramatic television has also produced an alternative set of urban images in recent years, images that are now taking their place alongside the classic, “crime on the streets” motif. In short, in addition to presenting viewers with images of urban mayhem, American television now offers a new vision of the city as a bourgeois playground—a bright-lights stage upon which popular fantasies of wealth, power, and distinction can be indulged.

Consider how Boston Legal handles the transition between segments. Coming out of commercial, the camera swoops over and between imposing steel-and-glass skyscrapers. Then an establishing shot anchors us outside an impressive office building, and we stare admiringly up from street level to the top floor offices of Boston’s most glamorous (and ridiculous) law firm. Together, these energetic shots of the urban landscape subtly communicate messages of vitality, power, and authority. This is the heart of the city, we are told. This is the place where big fish swim in a big pond and live big, important lives.

And on it goes. Sitcoms featuring twenty-to-thirtysomething casts—from Friends to Sex and the City to How I Met Your Mother—now seem contractually obligated to take place in Manhattan. Presented as an enticing landscape of bars, cafes, and exclusive boutiques, the city becomes a place to for middle-class college grads to challenge themselves and pal around with friends while building a life and career. It wouldn’t be nearly as exciting on Long Island.

Indeed, particular cities seem to act as “brands” communicating glamorous messages to favored TV audiences. If, for example, Seattle’s tourism officials trade on the city’s “dot.com” image of youthful, bohemian creativity, what better setting could there be for a show about young doctors finding their way? And if your franchise is flagging a bit, as MTV’s Real World has for years, filming in “name brand” cities—from San Francisco to London—can add spice to a tired idea.

In all cases, our young urban protagonists must be housed in trendy lofts located in gentrifying neighborhoods and pursuing the kinds of knowledge economy jobs that get urban planners so excited. The brave new urban world presented on American television is thus a resolutely upscale world of architects, lawyers, doctors, art dealers, and fashion editors. Given these images, who wouldn’t want to move to the big city?

We have indeed come a long way from “crime in the naked city.” Yet, this said, there is still something about this recent celebration of the gentrified city that rankles.

I think what bothers me is my suspicion that urban leaders have internalized these televisual images of the urban good life. When they think of “urban vitality,” they envision the city as a playground of upscale consumption and leisure. And, in doing so, they have increasingly committed themselves to policies of gentrification and displacement.

Indeed, one of the reasons that revitalization guru Richard Florida commands big lecture fees is that he tells city officials exactly what they want to hear. If you want to attract growth and prosperity, he argues, you need to turn your city into the kind of place that “the creative class” enjoys (and by “creative class” Florida means highly-skilled professionals very much like city officials themselves). Once you attract the creative class, Florida argues, high-end employers—who are always searching for deep pools of creative talent—will soon follow.[2]

So get busy, city leaders. Nurture those loft districts. Subsidize those museums and performance spaces. Turn key neighborhoods into real-life versions of Sex and the City, complete with art galleries, funky clubs, and sidewalk cafes. Urban vitality and prosperity await us all.

Well, maybe not all of us. As Neil Smith has pointed out, celebratory discourses of urban revitalization often work from a frontier narrative. In this story, upscale gentrifiers are viewed as urban “pioneers” and praised for bringing civilization, in the form of Starbucks and Pottery Barn, to the “urban wilderness.”

Of course, as Smith wryly notes, before the urban wilderness can be tamed, the “natives”—in the form of the inner-city poor and working-class—must be removed. But this time, in the new urban frontier, the only hint that the cavalry is coming to kick you out is the eviction note on your door.[3]

Ultimately, this is the dark side of prime time’s celebration of the gentrified city. If in the past, television portrayed an urban America at the mercy of a demonized underclass, today’s televisual city has been re-conquered by a phalanx of bourgeois-bohemians drinking soy lattes on the way to pilates class.[4]

In between the demonization and displacement of the urban working-class are the real, everyday challenges faced by families living in America’s cities through good times and bad. Their lives and dilemmas would make for some very compelling television, but, alas, it appears that the gentrifiers have moved in and the eviction notices are already up.

Image Credits:

1. Grey’s Anatomy

2. Boston Legal

3. Sex and the City – Dining Out

4. Sex and the City – Carrie Shopping

Footnotes:

[1]Steve Macek, Urban Nightmares: The Media, the Right, and the Moral Panic over the City (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

[2]Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class…And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2003).

[3]Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (London: Routledge, 1996).

[4]I owe the term “bourgeois-bohemian” (or “bobo” for short) to David Brooks, Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001).

No comments:

Post a Comment