Saturday, December 22, 2018

Apply Soon -- George Mason University's PhD Program in Cultural Studies

Monday, November 30, 2009

What is Value?

"The new economy brings information technology and the technology of information together in the creation of value out of our belief in the value we create" (p. 160).

Leaving out the cute play of words in the first half of the sentence (where Castells again argues for the centrality of information technology in reorganizing capitalism since 1970), Castells is making a key claim about the source of value in the contemporary economy.

Leading up to this quote, Castells argues that valuation -- that is, the social determination that company X or commodity Y is more or less valuable -- has become detached from objective measurements of profit and the return of dividends. Remember, he's writing in the late 1990s. This was a world where, in 1999, at the height of the dot.com bubble, the stock of a single company, Amazon.com, was worth more than twice as much as the entire Russian economy--this despite the fact that Amazon had yet to turn a profit. What gives? On what basis does the collective intelligence of global financial markets determine the value of assets, commodities, or firms?

Castells writes that "two key factors seem to be at work in the valuation process: trust and expectations" (p. 159). If the collective intelligence of investors trusts a firm and its directions, and if they have high expectations for future gains, they express this by raising the value of the firm. This is largely a subjective process -- I say "largely" because objective calculations of profitability, costs, and returns play into the "buzz" that investors and fund managers generate about firms, products, and services. But the subjective element is there, made up of "a vague vision of the future, some insider knowledge distributed on line by financial gurus and economic 'whispers' from specialized firms, conscious image-making, and herd behavior" (p. 159).

Yet the subjective nature of value creation -- the ability to increase the value of a firm not by producing more efficiently or selling more widgets but by simply building trust and increasing expectations in a social network -- does not necessarily mean we need to toss out the Marxian connection between labor and value. As Castells writes:

"within the logic of capitalism, the creation of value does not need to be embodied in material production. Everything goes, within the rule of law, as long as a monetized surplus is generated, and appropriated by the investor. How and why this monetized surplus is generated is a matter of context and opportunity...There is a growing de-coupling between material production, in the old sense of the industrial era, and value-making. Value-making under informational capitalism is essentially a product of the financial market. But to reach the financial market, and to vie for higher value in it, firms, institutions, and individuals have to go through the hard labor of innovating, producing, massaging, and image-making in goods and services. Thus, while the whirlwind of factors entering the valuation process are ultimately expressed in financial value (always uncertain), throughout the process of reaching this critical judgment, managers and workers (that is, people) end up producing and consuming our material world -- including the images that shape it and make it" (p. 160)

Thus, the source of all value is still human labor -- whether it is the application of human energies in material production or the application of human energies in the creation of new financial instruments, innovations, processes, or the symbols used to hype these instruments, innovations, and processes.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

What's Next for the Entrepreneurial City? Urban Revitalization, post-Richard Florida

As David Harvey has written, the ability of firms to move production and administration functions around the globe confers upon capital the ability to play localities off one another, in search of the best possible deal.

This in turn has forced urban leaders into fierce rounds of interurban competition, with each city trying to one-up all others by presenting to mobile capital the best possible “business climate.”

And so in the last thirty years we have seen city leaders embark upon a succession of entrepreneurial strategies designed to attract tourists, investment, and jobs to their cities—everything from corporate tax breaks and enterprise zones to new baseball stadiums and underground shopping malls.

However, as we speak, one strategy for enticing investment and economic growth into urban America stands head and shoulders above the rest. We are, in short, living in the era of Richard Florida.

Florida is an urban development and public policy scholar who first ascended to superstar status with the publication of his bestselling The Rise of the Creative Class.

Most of Florida’s analysis in this book is not new.

Like Daniel Bell, Alvin Toffler and countless others, he argues that global capitalism has entered a new phase, where the engine of economic growth comes not from industrial might and control of material resources, but from human creativity, innovation, and knowledge.

In the new knowledge economy, then, human creativity is now the decisive competitive advantage.

For this reason, a new class of workers has emerged to displace the proletariat as the central subject of capitalism.

This is Florida’s “creative class”—that is, a rapidly expanding and influential class of scientists, engineers, designers, artists, and knowledge professionals who get paid to develop new ideas, new technologies, and new solutions to old problems.

In the end, those firms and industries that effectively nurture and harness the intellectual firepower of the creative class will prosper and grow, while those firms and industries that shut it down will wither and die.

So what does all this mean for cities trying to turn around their economies?

Here Florida gets, well, creative. He argues, first off, that the old models of urban economic growth are wrong. You can’t attract high-tech firms and “knowledge” jobs by giving out tax breaks or building subsidized office space.

Instead, he argues, high-tech firms follow talent, not tax breaks.

They will move to those cities that offer them the deepest pools of creative labor.

So the key to urban prosperity paradoxically has nothing to do with attracting firms. It depends instead upon attracting the creative class.

If you attract the creative class, the firms and jobs will follow.

And here Florida turns from economic analyst to urban vitality guru. Building a vital city means delivering to the creative class the bourgeois-slash-bohemian lifestyles they crave.

And what do “creatives” want?

According to Florida, they want funky and diverse neighborhoods, interesting architecture, a vibrant arts and music scene, and endless recreational opportunities.

They want cappuccino bars and bike paths. They want their authentic urban grit and their sushi, too.

So if you want to attract knowledge jobs, you need to attract the creative class. And to attract the creative class, you need to turn your city into a “bourgeois-bohemian” playground.

As Jeffrey Zimmerman put it, “be hip and they will come.”

These ideas, it turns out, are like catnip for city leaders.

They can’t get enough of Richard Florida, and so he commands five-figure speaking fees and spends much of his time consulting with local governments and chambers of commerce on how to attract creative talent to their communities.

And they are indeed eating it up.

Now, to be sure, these ideas can be critiqued on a variety of fronts.

For instance, you can object to the way they essentially advocate a policy of state-sponsored gentrification, by cajoling city leaders to do everything possible to turn their urban neighborhoods into playgrounds for a particular class of affluent workers.

But my main question today is “what’s next?” In short, what happens when these ideas fail to deliver urban growth and prosperity to cities like Milwaukee, Buffalo, and Baltimore?

And why will they fail?

First, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that Florida is just plain wrong when he ties urban economic and population growth to attracting the “creative class.”

The first broadside came when Ed Glaeser, a Harvard economist, ran an analysis of Florida’s own data, and found that population growth in US cities was unrelated to the concentration of “creative class” occupations.

Glaeser also found that having a lot of bohemians living in your city doesn’t attract population growth either.

Cities that scored high on Florida’s “bohemian index” (an index which measures the number of artists working in a city) were no more likely to grow than those that scored low. What did matter was simply the total number of college-educated people in the city: the more BA degrees in a city, the faster the city grew.

Other more recent studies have been unable to support Florida’s claims as well.

Remember that Florida argued that young creative workers will migrate to cities which sport a vibrant bohemian “scene” and where they can find a concentration of other “creatives” like themselves.

But one recent study in Urban Affairs Review found that the in-migration of young knowledge workers was unrelated to both cities’ pre-existing concentration of creative class occupations as well as the city’s rank on Florida’s “bohemian index”

Second, there is the anecdotal evidence of cities who have tried valiantly to reverse their urban fortunes by appealing to young knowledge workers, but have failed miserably to produce any tangible results.

Jeffrey Zimmerman, for example, describes how the City of Milwaukee embarked on its own “creative city” strategy to stem the population and job losses associated with rust belt deindustrialization.

However, after: (1) building a riverwalk, (2) encouraging high-end housing development close to downtown, (3) providing seed money for creative class amenities like sidewalk cafes and pet daycare businesses, and (4) funding an urban branding campaign targeting young professionals and titled “we choose Milwauke”…the city has precious little to show for all this trouble.

In fact, Zimmerman reports that job losses across the board accelerated during the years in which Milwaukee’s leaders pursued this strategy—even in so called “creative” occupations.

His conclusion was that Milwaukee’s “creative city” effort indeed increased land values in two gentrifying downtown neighborhoods, but that this basically reshuffled affluent residents from one part of town to another.

So, again, my question is “what’s next?” What will be the next big solution to urban revitalization be? And will this solution have any hope of succeeding where others have failed?

After all, the track record of revitalization strategies is not inspiring:

*Urban renewal plans of the 1950s and 1960s

*The “fantasy city” strategies of the 1980s and 1990s, when cities built baseball stadiums, festival malls, and aquariums to attract tourists and build a positive image of place.

*And now the “creative city” strategies of Richard Florida.

None of these strategies have delivered on promises of steady urban population and broad-based economic growth.

For example, the last census showed that, despite the fact that central cities have stopped hemorrhaging residents and even grew from 1990 to 2000, suburban growth still outpaced urban growth, as it has for decades.

Close to home, despite embarking on a glitzy campaign to attract young, single, affluent workers in 2003, the District continues to loose population and jobs to the suburbs.

Today, the suburbs of Maryland and Virginia command a larger share of metropolitan jobs than ever before, and, for the first time, the sprawl of the Washington metro area has come within sight of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

By any standard, these public-private urban revitalization plans have been abysmal failures.

But, then again, perhaps I said “failed” too quickly.

My cynical side wants to suggest that although each of these revitalization strategies—the aquariums, the festival malls, and now the funky gentrified neighborhoods—failed to deliver on their promise of attracting global investment and reversing their declining urban fortunes…

…they actually succeeded in at least one of their aims: bringing public money into the service of local development actors and increasing the property values of politically-connected landowners.

So perhaps my true question is a cynical one:

What’s next? What new strategies will urban developers and landowners use to attract public money to support and expand their investments in urban real estate? And how will these subsidies be sold as a means of “saving the city” for us all?

Friday, February 27, 2009

Utopia on Lost

While Americans are working more hours than ever, wages for the bottom 40 percent of Americans have stagnated in the last 30 years.[i] Meanwhile, the rich get richer, and even the middle class has lost ground. Between 1979 and 2003, for instance, while the income of the middle fifth of American households increased slightly in inflation-adjusted dollars from $38,900 to $44,800, the average income of the top one percent of households more than doubled, from $305,800 to $701,500.[ii]

It’s a sobering picture. Still, these numbers do little to document the struggles that working families face in everyday life—including the feelings of desperation as productivity demands and working hours continually increase, [iii] as wages stagnate and collective benefits recede, and as flexible work schedules become a privilege reserved for the affluent and the tenured.[iv]

Perhaps not surprisingly, commercial television dramas in the USA have largely ignored the accelerating pace of class exploitation—most likely for reasons that are familiar to everyone. Advertisers want a good environment for promotional messages and brand integration, not to mention an audience packed with young, affluent viewers. Programs that frankly explore class issues seem unlikely to yield either of these conditions and thus die a silent death in the Hollywood pitch-room.

But yet, as I noted in my last column on Everybody Hates Chris, sometimes even American commercial television can surprise you. And sometimes, on magical occasions, a show can give you a powerful, if refracted and distorted, glimpse into a classless socialist utopia.

This brings us to the second season of ABC’s Lost. Like many Flow readers, I’m a fan of the show. The central conceit of Lost, as most of you probably know, is that forty-odd survivors of a plane crash find themselves marooned on a tropical island, cut off from civilization, and then menaced by a band of “others” whose origins and ultimate plans for the castaways remain a central mystery in the story.

Of all the show’s intriguing characters, I like Hurley (Hugo) Raez the best. Hurley—an overweight, heart-of-gold, SoCal guy—mostly offers comic relief in this dead-serious show, and for this reason, he’s not often the focus of the narrative. But when he is, it’s usually quite engaging.

The episode in question—Everybody Hates Hugo, oddly enough—begins with a montage of Hurley in “the hatch” (an underground bunker discovered by the castaways in season one) stuffing his face with snacks, peanut butter, and ice cream.

Hurley then awakens. His feeding frenzy was merely a dream—a dream fueled, we learn, by Hurley’s concerns about his new “job” on the island. It turns out the castaway’s nominal leader, Jack, has asked him to inventory the storehouse of food they had just discovered in the hatch. Until this inventory is done, Hurley must deny all requests for food from the other (hungry) castaways.

We quickly learn that Hurley is oddly tormented by this job. He first tries to keep the food secret. When word leaks out, he tries to avoid contact with others. When his friends find him and ask for food, he panics. At one point, he even tries to explode the storehouse with two sticks of dynamite. What gives?

The episode’s flashbacks offer an explanation. In the first flashback, we see Hurley win the lottery. An instant millionaire, Hurley nonetheless returns to his job at Mr. Cluck’s (a fast food chicken joint) without telling anyone, not even his mother. At work, his belligerent boss confronts him with surveillance tape footage that shows Hurley eating an unauthorized bucket of chicken. “You owe the company for an eight-piece dark meat combo, Raez,” the manager snarls.

Liberated by his lottery winnings, Hurley discards his hair net and promptly quits. His best friend and co-worker, Johnny, then quits in solidarity, and the two friends make a day of it. They hit the record store. Hurley asks out a cute girl. They steal 100 lawn gnomes and then spell out the words “cluck you!” on their boss’s front lawn.

All the while, Hurley keeps his newfound wealth a secret. Toward the end of their adventures, Hurley turns to Johnny and says, “Dude, promise me that no matter what happens, we’ll never change. This will never change.”

His friend, puzzled, duly promises, and they steer their van into the quickie mart where Hurley bought his lottery ticket. A camera crew is there interviewing the shopkeeper, who turns and recognizes Hurley: “that’s the guy! That’s the winner!” As the scrum of media and well-wishers press in on Hurley, the camera focuses on Johnny. His face is a heart-sinking mix of shock, envy, and anger.

Cut back to the island. Hurley’s friend Rose is attempting to stop him from blowing up the food. She can’t understand why he’d do such a thing. Hurley begins yelling:

Let me tell you something, Rose. We were all fine before we had any potato chips. And now we’ve got these potato chips. And now everyone’s going to want them! So if Steve gets them, Charlie’s pissed. But he’s not going to be pissed at Steve. He’s pissed at me!...And it’s going to be “what about us?” Why didn’t I get any potato chips?” C’mon help us out, Hurley…Then they’ll get really mad and start asking “why does Hugo have everything? Why should he get to decide? They’ll all hate me!

What is most intriguing is what happens next. Hurley finishes the inventory, and then approaches Jack with a proposal. Rather than ration the food, a little here, a little there, to the weak or to the strong, let’s just give it all away. To everyone. Right now. The episode thus ends with an uplifting montage of the castaways sharing the hatch’s bounty, smiling, laughing, and slapping Hurley on the back.

Fredric Jameson once wrote that “all contemporary works of art—whether those of high culture and modernism or mass culture and commercial culture—have as their underlying impulse…our deepest fantasies about the nature of social life, both as we live it now, and as we feel in our bones it ought rather to be lived.”[v]

What I felt in my bones when I watched this episode was a yearning for the collective life of the castaways. Whatever else happens, these people are in it together. When times are bad, they are bad for everyone. When times are good—like when Hurley liberates the hatch’s food—they’re good for one and all alike. If you catch two fish, you share the other one. If you hunt the boar, the whole camp celebrates. There are no separations of wealth and class—the separations that, in the flashback, ultimately split Hurley off from his friend Johnny.

(In this regard, it is instructive that the only remaining capitalist on the island—Sawyer—is treated as an outsider for much of the series due to his commitment to private property. Right after the crash, Sawyer hoarded the supplies he pillaged from the ruined fuselage, and he subsequently made many enemies as a result.)

Meanwhile, off the island, we live in a moment of profound ideological closure. The Democratic Party has fielded eight presidential candidates thus far, and all that any of them can offer us is the promise that our same anxious, privatized lives of moving back and forth from the “home box” to the “work box” in the “car box” will yield slightly more in terms of wages and benefits. Thus is the state of the American left.

But the dream of alternatives, the dream of “from each according to her ability, to each according to her need,”[vi] remains. In this regard, perhaps the most radical thing I’ve heard on TV in recent years—far more radical that anything I’ve heard from Clinton or Obama or even Edwards—came in Jack’s monologue to his fellow castaways soon after the plane crashed:

Everyman for himself is not going to work. It's time to start organizing. We need to figure out how we're going to survive here...Last week most of us were strangers, but we're all here now. And god knows how long we're going to be here. But if we can't live together, we're going to die alone.

Of course, as Jameson would point out, Jack was really speaking to us.

To be sure, moving beyond the mere dreaming of alternatives takes more than television. It will take a political movement that links the dreaming to the doing. But somehow I find hope in the fact that even this hyper-commercialized medium can, upon occasion, help nurture collective dreams through some very lean times.

[i] In 1973, for example, a high school diploma yielded an average inflation-adjusted wage of just over $14/hour. By 2006, that wage had dropped slightly. In fact, in 2006, over 24 percent of workers earned poverty-level wages Economic Policy Institute website, http://www.epi.org/datazone/06/wagebyed_a.pdf; http://www.epi.org/datazone/06/poverty_wages.pdf

[ii] Economic Policy Institute website, http://www.epi.org/datazone/06/avr_after-tax_inc.pdf

[iii] Economic Policy Institute webstie, http://www.epi.org/datazone/06/fam_wrk_hrs.pdf

[iv] AFL-CIO website, http://www.aflcio.org/issues/workfamily/workschedules.cfm

[v] Fredric Jameson, “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture,” Social Text, no. 1 (Winter 1979): 130-148.

[vi] Karl Marx, Marx/Engels Selected Works, Volume 3 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970): 13-30.

Friday, May 16, 2008

Urban Fortunes: Television, Gentrification, and the American City

As a student of both television and urban politics (admittedly an odd combination), I was struck by the prominent role played by the Seattle skyline. The image seemed to suggest, in short, that it mattered where this relationship drama was set. The inclusion of Seattle’s skyline (along with, of course, the ubiquitous Space Needle) meant something to the show’s fan base of college students. But what was that “something,” anyway?

Further “study” (i.e., watching TV, surfing YouTube) confirmed that Grey’s Anatomy was by no means alone. Establishing shots of glittering city skylines and vibrant urban street scenes proliferate on contemporary television—to the point where one might conclude six decades of rapid suburbanization have been abruptly reversed. Not quite. If many American central cities have stopped hemorrhaging residents in the last five years, population growth remains, as it has since the New Deal, a largely suburban phenomenon.

So what explains the seemingly sudden “back to the city” movement on American television?

One answer is that TV never left actually the big city. And this is true enough. The fate of the American metropolis has been a key subject of dramatic television for decades. Yet, until recently, as Steve Macek points out in his insightful new book, Urban Nightmares, media representations of the city have most often dwelled on the negative, depicting with seeming relish an urban America caught in a never-ending cycle of crime, drugs, and moral decay.[1]

During the Reagan era, for instance, Escape from New York presented moviegoers with a dystopian urban future in which the authorities had exhausted all solutions to the “urban crisis” and had instead turned the entire island of Manhattan into an open-air prison.

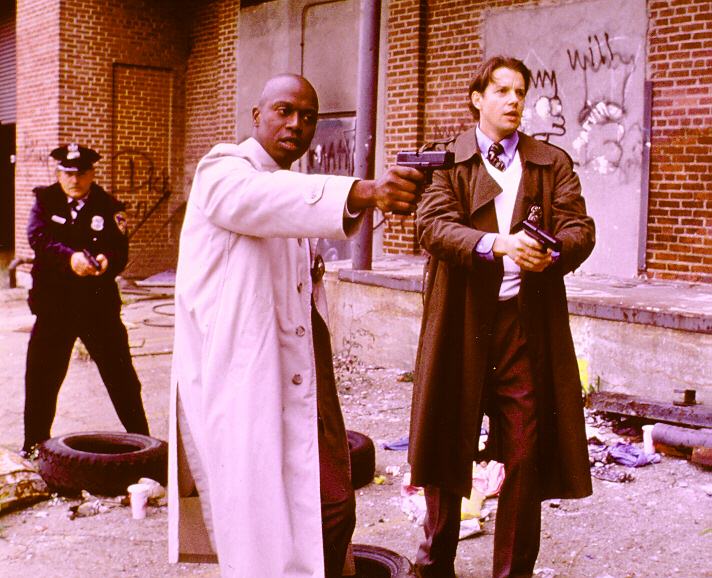

On television, 1980s cop dramas like Hill Street Blues and Homicide: Life on the Streets mined the same ideological vein, if from a slightly less reactionary position. On these shows, viewers were presented with an urban landscape bursting at the seams with disorder and deviance—the de rigueur drug dealers, gang bangers, and serial killers—all set in a crumbling urban landscape marked by graffiti, abandoned buildings, and homeless encampments.

If our heroes in these Reagan-era shows (almost always cops and prosecutors) gamely labored to sew up the moral and social fabric, suburban viewers knew their efforts would be for naught. There would in short be no solution, no stepping back from the urban brink.

For his part, Macek argues that these bleak media representations of the American city amplified conservative political discourses about the causes of the “urban crisis.”

Thoroughly mystifying the role global economic restructuring played in undermining urban economies, conservatives instead blamed the city’s poor for their own poverty, along the way constructing menacing (and thoroughly racialized) folk devils like the “welfare queen” and “drug kingpin.” In doing so, these discourses labored to consolidate white suburban support for “get tough” policies like welfare reform and the patently racist “war on drugs.”

To be sure, such reactionary images of a decaying, pathological inner city persist on American television. The opening sequence of Jerry Bruckheimer’s CSI, for example, trades explicitly in urban nightmares, interspersing shots of the Vegas strip with quick cut images of firing handguns, yellow-taped murder scenes, and forensic scientists looking thoughtfully at decaying bits of flesh.

Fans of the franchise know that in CSI-land, the streets of Vegas, Miami, and New York play host to the most gruesome murders imaginable, with human corpses offering up the secrets that eventually allow investigators to catch the bad guys. In such shows—NBC’s Law & Order franchise comes to mind as well— the urban landscape is still presented as a threatening space of violence, deviance, and moral decay.

Yet, it seems to me that dramatic television has also produced an alternative set of urban images in recent years, images that are now taking their place alongside the classic, “crime on the streets” motif. In short, in addition to presenting viewers with images of urban mayhem, American television now offers a new vision of the city as a bourgeois playground—a bright-lights stage upon which popular fantasies of wealth, power, and distinction can be indulged.

Consider how Boston Legal handles the transition between segments. Coming out of commercial, the camera swoops over and between imposing steel-and-glass skyscrapers. Then an establishing shot anchors us outside an impressive office building, and we stare admiringly up from street level to the top floor offices of Boston’s most glamorous (and ridiculous) law firm. Together, these energetic shots of the urban landscape subtly communicate messages of vitality, power, and authority. This is the heart of the city, we are told. This is the place where big fish swim in a big pond and live big, important lives.

And on it goes. Sitcoms featuring twenty-to-thirtysomething casts—from Friends to Sex and the City to How I Met Your Mother—now seem contractually obligated to take place in Manhattan. Presented as an enticing landscape of bars, cafes, and exclusive boutiques, the city becomes a place to for middle-class college grads to challenge themselves and pal around with friends while building a life and career. It wouldn’t be nearly as exciting on Long Island.

Indeed, particular cities seem to act as “brands” communicating glamorous messages to favored TV audiences. If, for example, Seattle’s tourism officials trade on the city’s “dot.com” image of youthful, bohemian creativity, what better setting could there be for a show about young doctors finding their way? And if your franchise is flagging a bit, as MTV’s Real World has for years, filming in “name brand” cities—from San Francisco to London—can add spice to a tired idea.

In all cases, our young urban protagonists must be housed in trendy lofts located in gentrifying neighborhoods and pursuing the kinds of knowledge economy jobs that get urban planners so excited. The brave new urban world presented on American television is thus a resolutely upscale world of architects, lawyers, doctors, art dealers, and fashion editors. Given these images, who wouldn’t want to move to the big city?

We have indeed come a long way from “crime in the naked city.” Yet, this said, there is still something about this recent celebration of the gentrified city that rankles.

I think what bothers me is my suspicion that urban leaders have internalized these televisual images of the urban good life. When they think of “urban vitality,” they envision the city as a playground of upscale consumption and leisure. And, in doing so, they have increasingly committed themselves to policies of gentrification and displacement.

Indeed, one of the reasons that revitalization guru Richard Florida commands big lecture fees is that he tells city officials exactly what they want to hear. If you want to attract growth and prosperity, he argues, you need to turn your city into the kind of place that “the creative class” enjoys (and by “creative class” Florida means highly-skilled professionals very much like city officials themselves). Once you attract the creative class, Florida argues, high-end employers—who are always searching for deep pools of creative talent—will soon follow.[2]

So get busy, city leaders. Nurture those loft districts. Subsidize those museums and performance spaces. Turn key neighborhoods into real-life versions of Sex and the City, complete with art galleries, funky clubs, and sidewalk cafes. Urban vitality and prosperity await us all.

Well, maybe not all of us. As Neil Smith has pointed out, celebratory discourses of urban revitalization often work from a frontier narrative. In this story, upscale gentrifiers are viewed as urban “pioneers” and praised for bringing civilization, in the form of Starbucks and Pottery Barn, to the “urban wilderness.”

Of course, as Smith wryly notes, before the urban wilderness can be tamed, the “natives”—in the form of the inner-city poor and working-class—must be removed. But this time, in the new urban frontier, the only hint that the cavalry is coming to kick you out is the eviction note on your door.[3]

Ultimately, this is the dark side of prime time’s celebration of the gentrified city. If in the past, television portrayed an urban America at the mercy of a demonized underclass, today’s televisual city has been re-conquered by a phalanx of bourgeois-bohemians drinking soy lattes on the way to pilates class.[4]

In between the demonization and displacement of the urban working-class are the real, everyday challenges faced by families living in America’s cities through good times and bad. Their lives and dilemmas would make for some very compelling television, but, alas, it appears that the gentrifiers have moved in and the eviction notices are already up.

Image Credits:

1. Grey’s Anatomy

2. Boston Legal

3. Sex and the City – Dining Out

4. Sex and the City – Carrie Shopping

Footnotes:

[1]Steve Macek, Urban Nightmares: The Media, the Right, and the Moral Panic over the City (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

[2]Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class…And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life (New York: Basic Books, 2003).

[3]Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (London: Routledge, 1996).

[4]I owe the term “bourgeois-bohemian” (or “bobo” for short) to David Brooks, Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001).

Saturday, October 13, 2007

Everybody Hates Chris and the (Overdue) Return of the Working-Class Sitcom

NOTE: I originally published this commentary on Flow TV: A Critical Forum on Television and Media Culture, an online journal published out of the Department of TV-Radio-Film at the University of Texas, Austin (www.flowtv.org). My thanks to the editors of this journal--graduate students, mostly--for inviting me to be a columnist over the past year.

NOTE: I originally published this commentary on Flow TV: A Critical Forum on Television and Media Culture, an online journal published out of the Department of TV-Radio-Film at the University of Texas, Austin (www.flowtv.org). My thanks to the editors of this journal--graduate students, mostly--for inviting me to be a columnist over the past year. One of the best things I’ve seen on television recently was shot from the perspective of a garbage can. This particular shot comes in the middle of the pilot episode of Everybody Hates Chris, a semi-autobiographical sitcom that chronicles the middle-school experiences of comedian Chris Rock in early 1980s

In the pilot, we learn the basic premises of EHC. It is 1982. The Rock family has just moved out of the projects and into their new home—a two-level apartment in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Young Chris is excited about the move and the adolescent adventures that await him now that he’s turned thirteen. His excitement vanishes, however, when his mother informs him that he’ll be taking two buses everyday to become the only black student at Corleone Middle School—all the way out in white working-class Brooklyn Beach.

In this way, two social spaces generate most of the show’s comic energy. Class issues are largely explored in Chris’s home life, while the show’s writers use Chris’s travails at Corleone to foreground questions of race.

This brings us to the garbage can. Early in the show, we learn that Julius Rock, Chris’s father, works two jobs and counts every penny. Julius, it turns out, has a particular talent for knowing the cost of everything. When Chris goes to sleep, Julius tells him, “unplug that clock, boy. You can’t tell time while you sleep. That’s two cents an hour.” When the kids knock over a glass at breakfast, Julius says, “that’s 49 cent of spilled milk dripping all over my table. Somebody better drink that!” And when someone tosses a chicken leg into the garbage, we see Julius peer over the rim, grab it, and exclaim, with a pained look on his face, “that’s a dollar nine cent in the trash!”

To be sure, as a former early 1980s middle-schooler myself, I enjoy the retro references to Atari, velour shirts, and Prince’s Purple Rain. But what I like most about EHC is how it foregrounds the experience of class inequality. Unlike other blue-collar comedies (e.g., According to Jim, Still Standing and King of Queens) which signify their characters’ working-class status via lifestyle choices (i.e., wearing Harley shirts, drinking beer, listening to Aerosmith, etc.), EHC generates much of its comedy directly from the class-based experience of struggling paycheck to paycheck and never having enough to pay the bills.

And so, in one episode, we see Julius buying the family’s appliances from Risky, the neighborhood fence, because the department store is simply out of reach. In another, Julius and Rochelle (Chris’s mother) agree to give up their luxuries (his lottery tickets and her chocolate turtles) in order to pay the gas bill. Things go haywire, however, when Rochelle (now reduced to getting her sugar fix from pancake syrup) catches Julius sneaking out to play the Pick 5.

And during one dinner, when Chris finally gets up the courage to ask for an allowance, Julius delivers a lecture familiar to every working-class kid. “Allowance? I allow you to sleep at night. I allow you to eat them potatoes. I allow you to use my lights…Why should I give you an allowance, when I already pay for everything you do?!”

What makes this focus on class all the more remarkable is that it comes to us in the form of a so-called “black sitcom.” As Timothy Havens notes in his study of the global television trade, international buyers looking to pick up American sitcoms strongly prefer “universal” to “ethnic” comedies (their words, not Havens’). As Havens quickly makes clear, however, the term “universal” is essentially code for white, middle-class, family-focused shows of the Home Improvement variety.

Thus, in the international TV marketplace, a white, middle-class experience becomes universalized as something that will appeal to “everyone.” Steeped in this discourse of whiteness, distributors reflexively brand as “too ethnic” any shows that deviate from this norm, including especially sitcoms that, as Havens writes, “incorporate such features as African American dialect, hip-hop culture…racial politics, and working-class…settings.”[1]

Given the important role played by international sales in the profitability of American television programs, this hostile distribution environment makes it less likely that shows with African-American casts will be produced in the first place.

The breakthrough success of The Cosby Show in the 1980s, of course, pointed a way out of this particular cultural and commercial box.

As Sut Jhally and Justin Lewis note, Cosby struck an implicit bargain with white audiences in the Reagan era. In exchange for white viewers inviting the Huxtables into their homes, the show’s producers would banish explicit references to the politics of race and keep the narratives focused on “universal” family themes. You’ve seen the show. Theo gets a “D” in math and receives a stern lecture from Cliff. Cliff’s attempt to cook dinner for the family ends in disaster. A slumber party for Rudy gets hilariously out of hand.

But, equally importantly, because white audiences have historically associated poverty with “blackness” and coded middle-class status as “white,” The Cosby Show placed these family-friendly stories in a context dripping with wealth and class privilege. In the end, this complex interpenetration of class and race in the dominant cultural imaginary allowed many white viewers (who might otherwise have been reluctant to watch a “black sitcom”) to read the Huxtables—an upscale African-American family focused on the peccadilloes of everyday life—as “white” and therefore “just like us.”[2]

The commercial fortunes of The Cosby Show have thus left an ambiguous legacy. Its path-breaking success has undoubtedly provided subsequent producers of African-American sitcoms with rhetorical ammunition to take into the pitch room (“Cosby made $600 million in its first year of syndication!”).[3] In an industry built on the endless repetition of past success, this is no small contribution.

Yet the middle-class, family-focused formula for African-American sitcoms—the model that signifies “universality” to international distributors and buyers—has also proven to be an ideological straight-jacket. To get on the air, in short, class must be dismissed. Thus, shows like The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, The Bernie Mac Show, and My Wife and Kids reproduce the upscale Cosby formula in exacting detail. Even programs like Girlfriends—shows that jettison family-focused themes for a more hip and youthful sensibility—nonetheless take great pains to place characters into high-end, even lavish, settings.

This raises the question of how EHC got on the air in the first place. Undoubtedly, the star power of Chris Rock, the show’s co-creator and narrator, played a central role. This said, I would love to know more about exactly how artists like Chris Rock draw upon their accumulation of symbolic capital—including their professional prestige, their network of connections, and their track record of commercial success—in order to overcome the ideological limitations of the industry’s commercial “common sense”

Indeed, perhaps this is a question that future political-economic work in television studies could productively explore. If we knew more about the conditions in which such accumulations of symbolic and social capital can be strategically applied to open new ideological spaces in the industry, we could create cultural policies that encourage this process.

In the meantime, I’m rooting for the future success of EHC. Admittedly, I’ve only seen the first season DVDs, so disappointments may be waiting. Still, for placing the struggles of working families at the center of its narratives, and for presenting the working-class experience as more than a matter of consumer choices, EHC has earned a valued place in my Netflix queue.

Image Citation:

1. Cast photo -- http://www.magneticmediafed.com/?cat=43

[1] Timothy Havens, “‘It’s Still a White World Out There’: The Interplay of Culture and Economics in International Television Trade,” Critical Studies in Media Communication, vol. 19, no. 4 (December 2002): 387.

[2] Sut Jhally and Justin Lewis, Enlightened Racism: The Cosby Show, Audiences, and the Myth of the American Dream (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1992).

[3] The $600 million revenue figure came from http://movies.yahoo.com/movie/contributor/1809120796/bio.

Monday, October 1, 2007

Commercial Media, Media Reform, and an Arlington Church Basement

NOTE: I originally published this commentary on Flow TV: A Critical Forum on Television and Media Culture, an online journal published out of the Department of TV-Radio-Film at the University of Texas, Austin. My thanks to the editors of this journal--graduate students, mostly--for inviting me to be a columnist over the past year.

NOTE: I originally published this commentary on Flow TV: A Critical Forum on Television and Media Culture, an online journal published out of the Department of TV-Radio-Film at the University of Texas, Austin. My thanks to the editors of this journal--graduate students, mostly--for inviting me to be a columnist over the past year.The recent successes of the media reform movement have been, in a word, stunning. To be sure, most of the victories have been on defense. Reformers fought off Michael Powell’s drive to annihilate media ownership restrictions in 2003, and big telecomm’s more recent attack on net neutrality—once viewed as irreversible—has been handed a series of improbable defeats. [i]

These are both big wins. So it would seem that the public’s disgust with media commercialism and their distrust of industry motives is both wider and deeper than many expected. Okay, I’ll admit it. I was surprised (if pleasantly so).

But perhaps I shouldn’t have been. The popular critique of media commercialism has deep cultural roots, and at the heart of this criticism is a rejection of the basic amorality of financial capital. In this critique, it is not merely—or even primarily—economic inequality or even labor exploitation that offends. It is rather the suspicion that, in market societies, every value, every principle, ultimately becomes subordinated to the cold calculus of profit.

This holds as true in the media system as it does anywhere else. If advertisers want to promote alcohol to teens, corporate media is there to help. If junk food firms want to sponsor Dora the Explorer, Nickelodeon is happy to oblige. If it’s a choice between covering climate change or filling the newscast with plugola, well, that’s no choice at all. Plug away! You don’t have to be fire-breathing radical to be disgusted with the moral consequences of media commercialism.

This last point became clear to me earlier this month as I was delivering a lecture in an

Initially grumpy about this intrusion on my winter break, I slowly warmed to the task. Like many Flow readers, I am sure, I teach my department’s required course in “mass communication” theory, and once during each semester we discuss the research and policy debates over media violence. The meat of the lecture would thus be pretty straightforward. These parents would essentially want to know if letting Johnny and Jane watch Justice League would inspire them to knock the other kids about the playground and land them in successive time-outs. Although this may not be the most interesting question to ask about media violence, the behavioral research on this question is nonetheless crystal clear (the answer is “yes, a little more likely”). [ii] Get out the media professor boilerplate.

At the same time, however, it began to dawn on me that I was being presented with an intriguing opportunity for, bluntly, political subversion. For I quickly realized that one of the questions parents would have would be “why all the violence, anyway?” This is a natural question, especially given the consistent finding that children’s programs contain more acts of violence per half hour than prime time shows. [iii] What could possibly motivate producers of children’s narratives to do such a thing?

The current political environment offers two major answers to this question. One argument—call it the cultural conservative argument—holds “the liberal

So here was my chance to present an argument on media violence that held commercial producers and global media firms culpable. And to a group of

Still, to be honest, I was pretty nervous about delivering Gerbner’s argument. Often, the gut instinct on these matters—as I’ve seen in class a thousand times—is to blame the parent. (Or, if you’re a parent, those “other” parents out there). If you don’t like children’s television, don’t let your kid watch it.

What I found, however, was just the opposite. These parents seemed to connect with the commercial explanations for the level of violence on children’s shows. It made sense to them. It made them angry. During Q&A, many parents expressed their desire for a media environment that did not relentlessly undermine their attempts to teach values like compassion and nonviolence.

One parent even said what I’d been secretly feeling for a long time: “why shouldn’t I be able to sit my kids in front of TV for a half hour while I do the dishes?” It seemed absurd to her that programming meant for children should require the co-presence of a vigilant parent, always at the ready to explain why his or her child shouldn’t take to heart television’s toxic lessons about aggression and violence.

Perhaps most tellingly, as I was wrapping up, I projected the now-iconic image of the “branded baby” on the screen and mentioned that I would be happy to come back and talk about children and advertising. More than one parent said they were more concerned about advertising and marketing than about aggression and violence.

All in all, this experience has led me to think more carefully about the rhetoric of the progressive-left media reform movement. The movement does, I think, a fine job of delivering what you might call the “public sphere” critique of commercial media. And rightly so. The criminal failure of the current system to provide an open forum form democratic debate and dialogue indeed deserves our ruthless criticism.

At the same time, progressive media educators and reformers have been less comfortable, it seems to me at least, with engaging in a moral critique of commercial media. Perhaps it comes from a reasonable fear of strange political bedfellows. It's not often, in short, that you see liberal progressives and cultural conservatives on the same side of an issue.

This said, I do think it is immoral to advertise junk food to kids. I do think it is wrong for media firms to accept alcohol ads on programs they specifically create with teens in mind. I indeed have a moral objection to children’s programs that divide the world in the “good” and “evil” and then celebrate aggression as the only effective way to protect “us” from “them.” (sound familiar, anyone?)

These are values that many people share. And if some folks have yet to make the connection between the commercial structures of the industry and these objectionable marketing and programming practices, the ideological ground for cultivating these sorts of connections is, in my view, fertile.

After all, the suspicion that an all-consuming pursuit of property and wealth is fundamentally amoral and dehumanizing can be found in more places than radical political theory. It is a suspicion also voiced with no small amount of power in the Christian gospels themselves. In fact, many of Jesus’ parables often dramatize the spiritual costs of putting material wealth ahead of our obligation to serve one another. In one particularly blunt example, a rich man, having spent his life ignoring a beggar’s pleas for food and shelter, is sent upon his death to an eternity of torment. In another, Jesus ends by making the point clear: you cannot serve two masters. You must choose between God and Money.

This is a point upon which limited, short-term, pragmatic coalitions can be built. Consider conservative evangelicals, example. As Andrea Press and Elizabeth Cole found in Speaking of Abortion, many evangelicals indeed accuse commercial media of undermining their conservative beliefs with regard to faith, family, gender, and sexuality. [iv]

Yet, interestingly, the authors report that evangelicals also object to television’s soulless materialism, its relentless commercialism, and its celebration of accumulation as an end in itself. And it is this contradiction in the wider conservative movement—this uneasy tension between the Chamber of Commerce’s religious devotion to markets and wealth and the working-class evangelical’s devotion to, well, Jesus—that merits some serious probing by progressives.

There is reason to be optimistic on this front. Indeed, one of most important features of the contemporary media reform movement is its refreshing lack of traditional lefty isolationism and orthodoxy. Free Press once allied with the NRA, for goodness sake.

In this spirit, if left-progressives speak openly about their own moral objections to the commercial media environment, and if they work to connect these concerns to the economic structures that generate this environment, they will be doing more than venting their spleens. They will be widening the constituency for media reform.

[ii] See especially C. Anderson, et al., “The Influence of Media Violence on Youth,” Psychological Science in the Public Interest, vol. 4, no. 3 (December 2003): 81-109.

[iii] B. Wilson, et al., “Violence in Children’s Television Programming: Assessing the Risks,” Journal of Communication, vol. 51, no. 1 (March 2002): 5-35.

[iv] Andrea Press & Elizabeth Cole, Speaking of Abortion: Television and Authority in the Lives of Women (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).